Common AI Agent Architecture Patterns

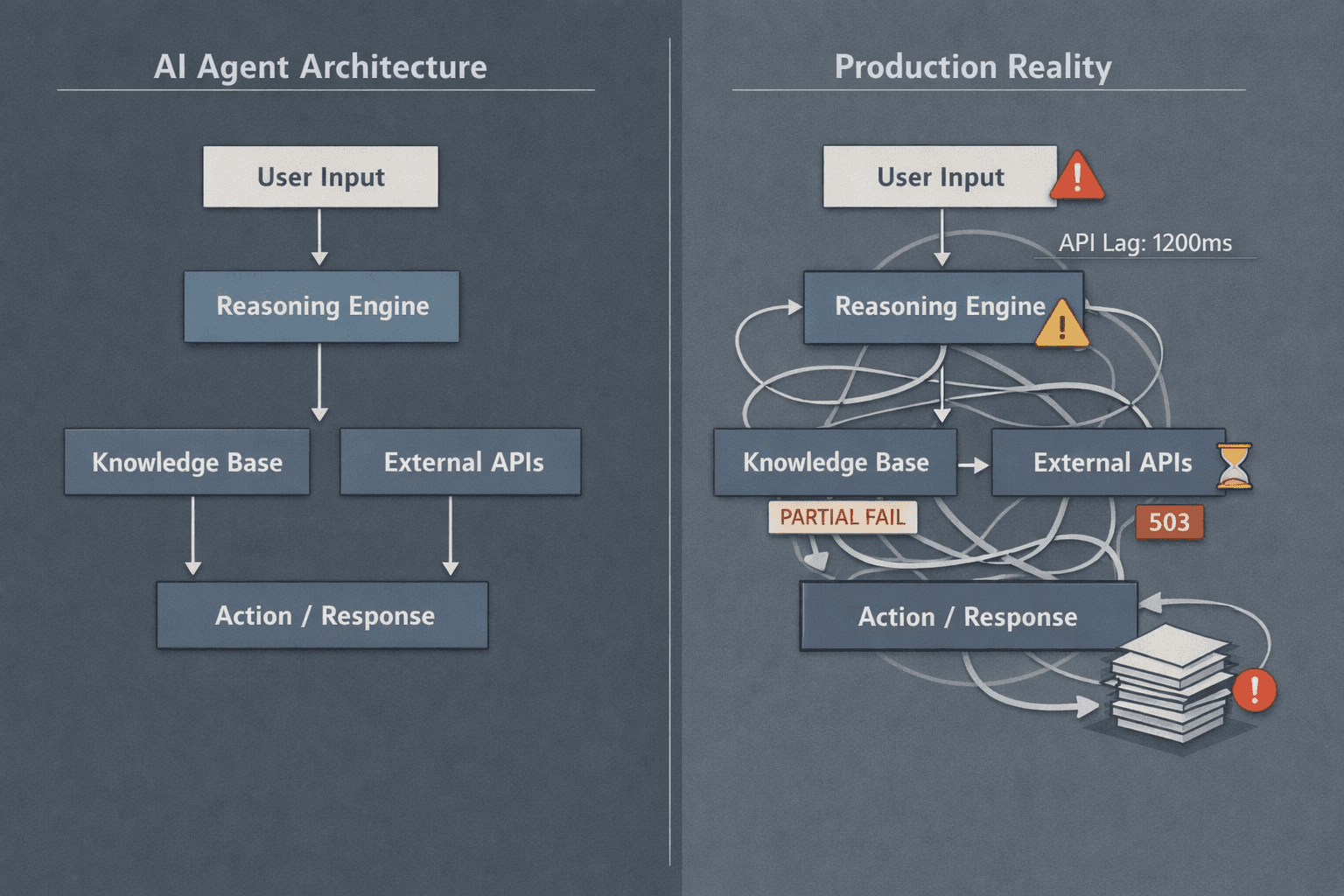

Most AI agent architectures don’t fail because the model is weak. They fail because the architecture assumes the world is cleaner than it is. Diagrams behave. Production systems don’t. Latency spikes, tools half-work, APIs lie, and users don’t follow scripts. The gap between a tidy agent flowchart and a system that survives a Tuesday afternoon is where most teams quietly give up. That gap isn’t about prompt quality. It’s about control, state, and knowing where intelligence should stop and software should take over. If you miss that distinction early, no amount of clever orchestration will save you later.

How AI agent architectures work in production

In production, an AI agent is not a magical decision-maker floating above your system. It is a component embedded inside a larger software organism, subject to the same constraints as everything else. The moment you deploy, the agent becomes part of an ecosystem that includes queues, databases, observability pipelines, rate limits, and human escalation paths. This is where most “agentic” demos quietly break down.

What actually happens is less glamorous. An input arrives, context is assembled from state and memory, the model proposes an action, and then a deterministic layer decides whether that action is allowed to execute. That decision layer matters more than the model. Without it, your agent is just a confident intern with production access.

In real systems, planning and execution must be separated even if the framework pretends otherwise. The planning loop can be probabilistic and messy. The execution loop cannot be. Execution needs retries, idempotency, timeouts, and clear rollback behavior. When teams blur these loops, failures cascade. A single hallucinated tool call can poison state, which then feeds the next step, which compounds the error. This is why agent systems that look elegant on paper often degrade non-linearly once traffic increases.

Memory design is another place where theory collapses into practice. Long-term memory is rarely a vector store queried freely by the agent. In production, memory is scoped, filtered, and often summarized aggressively before the model ever sees it. You are not building a mind. You are building a context budget allocator with opinions. Teams that treat memory as an open-ended recall system usually discover too late that relevance decay is real and expensive.

Failure handling is the final reality check. Agents fail quietly unless you force them to fail loudly. Silent retries, partial tool responses, and ambiguous model outputs must be surfaced as first-class signals. If your agent architecture doesn’t assume failure as the default state, it will surprise you in the worst possible way.

This is usually the moment teams realize they are not building an agent, they are building an orchestration system with an LLM embedded inside it. That realization tends to separate hobby projects from systems that scale, and it’s also where many teams go looking for a deeper practical guide to AI agents because intuition alone stops being enough.

Best AI agent architecture patterns for real projects

After seeing enough systems fail for similar reasons, certain patterns emerge that consistently survive contact with production. Not because they are clever, but because they are boring in the right places.

The most resilient pattern is the constrained single-agent with a strong orchestration layer. One model, one clear role, limited tool surface area, and a deterministic controller that owns state transitions. This pattern wins because it minimizes uncertainty. The agent reasons, but the system decides. Tool calling is gated, validated, and often simulated before execution. Planning happens in small increments, not grand multi-step fantasies.

Another pattern that works is the planner–executor split, but only when the boundary is enforced strictly. The planner produces an explicit plan artifact that is stored, inspected, and sometimes rejected. The executor does not reason. It follows instructions like a machine. This reduces the blast radius of bad reasoning and makes observability tractable. You can answer questions like “why did this happen” without replaying the entire conversation in your head.

Event-driven agent architectures also hold up well, especially in environments with asynchronous workflows. Here, the agent reacts to events rather than owning the entire flow. Each invocation is short-lived, stateless by default, and reconstructs context from authoritative sources. This avoids the creeping complexity of long-running agent sessions that accumulate invisible assumptions.

What consistently fails is the everything-agent. One agent to plan, reason, execute, remember, retry, and explain itself. This pattern collapses under load because every concern becomes entangled. Debugging turns into archaeology. Teams often reach for more prompts or more memory when the real problem is architectural overreach.

Frameworks like LangGraph and the OpenAI Agents SDK exist because teams keep rediscovering the same constraints. They offer structure around state transitions, tool calling, and failure handling, but they do not absolve you from making hard decisions. If you want a grounded comparison of how these frameworks approach orchestration and control, there’s a solid breakdown in agent orchestration frameworks that’s worth reading with a critical eye.

Single-agent vs multi-agent systems in practice

Multi-agent systems are seductive. They promise specialization, parallelism, and emergent intelligence. In practice, they mostly promise coordination problems. Every additional agent introduces new failure modes, new synchronization issues, and new questions about authority. Who decides when agents disagree? Who owns shared state? Who is allowed to act?

Single-agent systems dominate production for a reason. They are easier to reason about, cheaper to operate, and simpler to observe. When something goes wrong, you have one chain of reasoning to inspect. For most business workflows, this is enough. The complexity of the domain rarely justifies the complexity of multiple autonomous agents.

Multi-agent architectures do make sense in narrow cases. Research workflows where exploration matters more than determinism. Simulations where agents represent independent actors. Large-scale planning problems where decomposition is natural and coordination costs are acceptable. Even then, successful systems treat agents as workers, not peers. There is almost always a supervising layer that arbitrates outcomes and enforces constraints.

In real projects, teams often start with a single agent, prematurely scale to multiple agents, then quietly collapse back to one with better tooling. The lesson is not that multi-agent systems are useless. It’s that autonomy is expensive, and you should spend it deliberately.

State management becomes the breaking point. Shared memory between agents sounds powerful until you realize you’ve built a distributed consistency problem on top of a probabilistic system. The moment you need locking, versioning, or conflict resolution, you are no longer doing AI work. You are doing distributed systems engineering, and the agent is the least reliable part of the stack.

Observability suffers too. Tracing a failure across three agents, each with its own context window and reasoning style, is not for the faint of heart. Unless your team is already mature in distributed tracing and structured logging, multi-agent systems will slow you down rather than speed you up.

Where planning loops quietly sabotage execution

One of the more subtle failure patterns I keep seeing involves overconfident planning loops. The agent produces a beautiful multi-step plan, complete with contingencies, and everyone feels good. Then step three fails because an external API returns something unexpected, and the entire plan becomes invalid. What happens next determines whether your system is resilient or brittle.

In fragile systems, the agent tries to re-plan from corrupted state. It assumes previous steps succeeded when they partially failed. Errors compound. Logs become unreadable. In resilient systems, the plan is treated as a hypothesis, not a contract. Execution checkpoints validate assumptions continuously. When something diverges, the system resets to a known-good state and asks the agent to reason again with updated facts.

This is where planning vs execution loops stop being an academic distinction and start being an operational necessity. The planning loop should be cheap, discardable, and restartable. The execution loop should be conservative, observable, and boring. Mixing them is how you get elegant failures that no one can explain.

A brief digression from a failed deployment

A few years ago, we built an agent to automate internal support triage for a mid-sized SaaS company. On paper, it was clean. One agent handled intake, classification, tool calls, and responses. Early demos were impressive. The system felt alive.

Then real traffic arrived. Edge cases piled up. A misclassified ticket triggered the wrong tool call, which updated the wrong record, which then fed back into memory. The agent became confidently wrong in subtle ways. Support metrics degraded slowly enough that no one noticed at first. By the time alarms went off, trust was gone.

We rescued the system by doing something unglamorous. We split reasoning from action. We reduced the agent’s authority. We added a deterministic validation layer that rejected most tool calls. Accuracy improved overnight, not because the model got smarter, but because the architecture got humbler.

That experience reinforced a pattern I now default to: let the agent think, but never let it be in charge of consequences without supervision. Once you internalize that, most architectural decisions become clearer.

Tool calling, MCP, and the illusion of autonomy

Tool calling is where agent architectures either mature or implode. Giving an LLM access to tools feels empowering until you realize tools are side effects wrapped in APIs. Every side effect has cost, latency, and risk. Treating tool calls as mere extensions of reasoning is a category error.

In production systems, tool calls should be explicit, typed, validated, and logged independently of the model’s reasoning. The model proposes. The system disposes. This is why protocols like MCP (Model Context Protocol) matter. They impose structure on how tools are described, invoked, and audited. Not because structure is fashionable, but because ambiguity is expensive.

This is exactly where teams move beyond ad-hoc tool schemas and start adopting formal contracts like MCP — a pattern we break down in detail in using MCP to let LLMs call real tools , including where it helps and where it quietly adds overhead.

Autonomy is often confused with effectiveness. The most effective agents I’ve seen are tightly constrained. They know what they are allowed to do and, just as importantly, what they are not. This constraint improves reliability, reduces hallucination impact, and makes failures legible.

Observability is the real differentiator

If there is one area where strong teams consistently outperform weak ones, it’s observability. Not dashboards for vanity metrics, but deep visibility into agent decisions, state transitions, and tool outcomes. You should be able to answer why an agent acted the way it did without replaying prompts manually.

This requires structured logs, traceable state IDs, and clear boundaries between reasoning and action. It also requires discipline. Every shortcut you take early will tax you later. Observability is not an add-on. It is part of the architecture.

When teams complain that agents are unpredictable, what they usually mean is that they are blind. Once you instrument properly, behavior becomes explainable, even if it remains probabilistic.

Closing perspective

AI agent architecture is less about intelligence and more about restraint. The systems that survive production are not the ones with the most autonomy, the most tools, or the most elaborate reasoning chains. They are the ones that respect software fundamentals, assume failure, and treat the model as a powerful but unreliable collaborator.

If you design for that reality, agents can be transformative. If you don’t, they will fail quietly, expensively, and at the worst possible moment.

Sometimes progress comes faster with another brain in the room. If that helps, let’s talk — free consultation at Agents Arcade .

Majid Sheikh is the CTO and Agentic AI Developer at Agents Arcade, specializing in agentic AI, RAG, FastAPI, and cloud-native DevOps systems.